Mark Adams is a Liverpudlian working in a US federal library, and spends his life educating visitors on the legacy of President Harry S. Truman.

Working at the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum in Missouri for 27 years, and having recently been promoted from educational director to the museum’s curator, Mark is a long way from his job teaching in a Liverpool secondary school, over three decades ago.

Mark said: “I grew up in Liverpool, and some of the accent is still there, and I went to Wolves [then a polytechnic] in 1982. I had an interview at Wolverhampton to take a degree in humanities, history and geography, and, as a big Mark Adams football fan, doing that near Molineux [Wolverhampton Wanderers’ stadium] was eye-opening and appealing to me.

“My major was history, and my career definitely benefitted from the research side of the course, as well as from the professors who really pushed the idea of using original materials, primary sources. Learning how to use those materials effectively stuck with me as I went into my career.”

Despite his Liverpool roots, Mark has family in the United States. After visiting them over 30 years ago he “kind of” began applying for a green card, eventually married an American woman, and moved over in 1991.

With his background in teaching and history, he first worked at the Kansas State Museum, then six years later came to the Truman Library where he has been ever since.

Mark explained: “I was looking to go back into teaching. That’s what I was trained to do, but to do that they wanted me to go back to university and do more courses, and I was like, I’ve done that, I don’t need to go back. That’s when I got a contact about working in museum education.

“It’s still teaching, just with different students every day, and with an emphasis on showing teachers how to use the museum, the library, and the archive side of things. One of the things I learnt from going to Wolverhampton was how to use primary sources when I did my dissertation.”

The library is not a traditional public library, but an archives and museum collection. It is part of a long-running tradition in the US for presidents to establish a presidential library to house the archive, documents, and artifacts related to their presidency.

When Truman retired, he was working here at the Truman Library.

Truman left office from the White House in 1953, spent four years raising private money without government assistance, then opened the building in 1957. Mark said: “He donated everything: all his government documents and communications. He even donated his clothing, shoelaces, and glasses – everything.

Then the archivist started collecting materials from people that were in his cabinet, doing oral histories and interviews with people who worked with him.”

When he died in 1972, he was living just four streets away from the museum, and Mark said that one of the biggest “treasure troves” of Truman’s items was the collection of letters he wrote to his wife.

“They started dating in 1910, and of course he was the president from 1945 to ’53, and we have letters dating from 1910 to 1957 that he wrote directly to her. There are more than 1,300.

“Some people don’t realise that he’s the only president to have served in combat in World War One, so he was on the ground in France fighting but writing letters to his wife. We have all those letters, all those from the 20s and 30s, all those when he was the president, and afterwards in retirement. On the archive side, that’s kind of the richest collection that we have.”

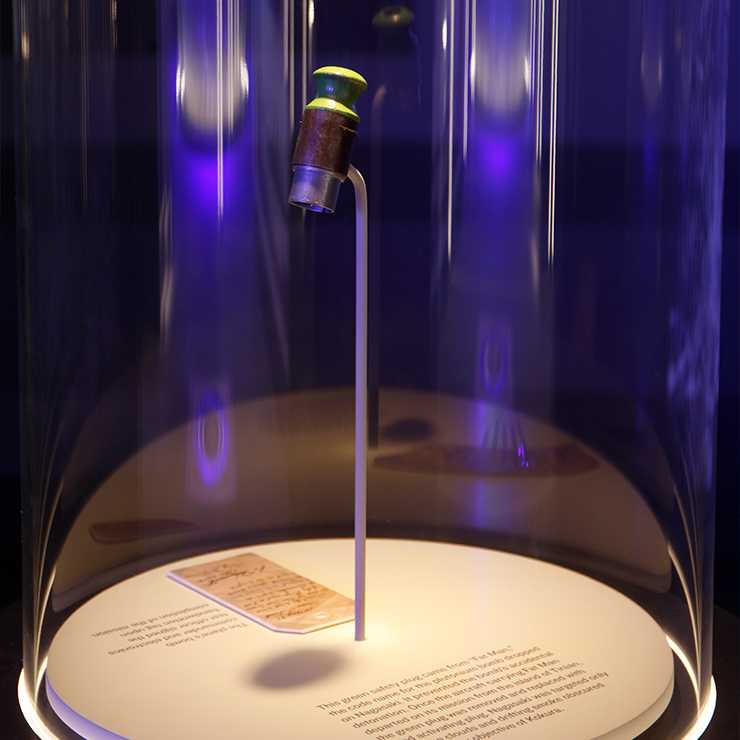

Mark’s favourite parts of the museum are two powerful reminders of the immense pressures of being the president: a safety plug and a Purple Heart honour.

He explains: “The plug is from the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, and it made the bomb safe to fly on the plane. Before it was detonated, they took the safety plug out and put the activating plug in. It’s just a little green plug, but the story it tells is remarkable.

“We also have a letter from a father whose son was killed in the Korean War, which was incredibly critical of Truman, blaming him for his son’s death. He returned the Purple Heart his son was posthumously given and at the end of the letter said, I wish your daughter had received the same treatment as my son. When Truman retired, he was working here at the Truman Library, and when he died, we found it in his desk.”

A key takeaway from Mark’s experience at the University of Wolverhampton has formed the foundation of his career in the US, where he brings creativity to a role in the federal government and helps bring history to life for new people every day.

After receiving his promotion to museum curator, Mark said: “The previous curator retired after 40 years, so I certainly have some big shoes to fill! I’m excited for the challenge and the next phase of my career.”

Mark may be right about having big shoes to fill, but with his passion for his role, he’ll no doubt live up to Truman’s own advice: “Do your best. History will do the rest.”