There are relatively few topics which remain taboo in the Western world, but one which is certainly not talked about, perhaps as much as it should, is female genital mutilation (FGM), sometimes referred to as ‘cutting’. The World Health Organisation describes FGM as “all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for nonmedical reasons.

Often a source of mystery to cultures where it isn’t practised – and of myth and misinformation in those where it is – alumna Fatou Baldeh, MBE, is working to empower Gambian women and girls through advocating for the protection of their sexual and reproductive health and rights; and raising awareness on the impact of violence against women and girls including harmful traditional practices such as FGM.

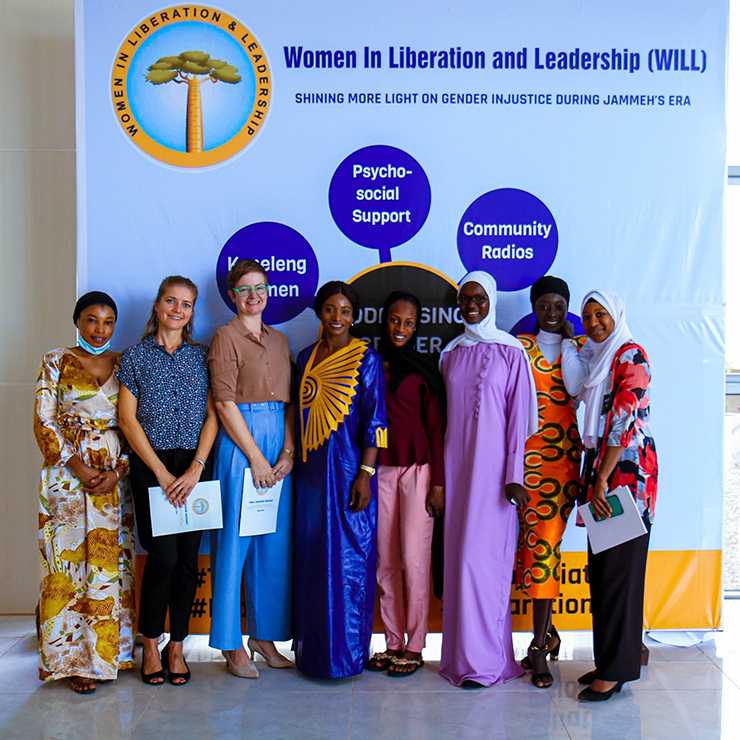

Fatou, founder and chief executive officer of Women in Liberation and Leadership (WILL), which works to end FGM and other forms of violence against women and girls, studied Psychology and Health Studies at the University. She was awarded an MBE in recognition for her contribution and work against FGM, which was made illegal in The Gambia in 2015. We spoke to her about her own experiences and her inspiring work.

“Wolverhampton was my first access to higher education. I studied for a BSc (Hons) Psychology and Health Studies at Wolverhampton City Campus between 2005-2009. My fondest memories are those that I spent with friends I made during the course. I particularly enjoyed learning about research methods and issues related to gender-based violence, which really set the foundation to my career.

“After completing my degree at Wolverhampton, I returned to The Gambia, working as a United Nations volunteer with UNICEF Gambia Country Office. There I learnt about the sexual and reproductive health issues affecting the health and development of Gambians, especially women. This inspired me to undertake a MSc in sexual and reproductive health and rights at Queen Margaret University in Edinburgh.

“As a requirement for my Master’s, I conducted my dissertation on FGM and obstetric care in Scotland. My dissertation was one of the first major pieces of research on FGM in Scotland, attracting substantial attention. Because of the publicity around the report, the equalities committee of the Scottish Government held an investigation on the issue and invited me as an expert witness. I made major contributions and many of my suggestions were put in place.

"I conducted further research on FGM with practising communities in Scotland, working with a team of women-led organisations to develop FGM resources for training and public education. These resources are now being used across Scotland to provide training to frontline professionals including the police, health care staff, social workers, students, border agency staff etc on how to best manage and support women and girls who have undergone, or are at risk of FGM in Scotland.

“In recognition for my contribution and work against FGM and support to migrant women in Scotland, I was awarded a Most Excellent Order of The British Empire (MBE) by Her Majesty the late Queen in September 2019.

“I wouldn’t say I was always interested in women’s rights – how can you when you grow up in a community where the low status of women is normalised? I didn’t know anything different, so I never questioned the inequalities that existed. Nonetheless my father, although not formally educated, was a strong supporter of educating his daughters. So, I became the first female in my family to attend school.

“As I accessed higher education, I started to analyse the injustice and discrimination that women and girls faced: I began to ask questions. Questions about harmful socio-cultural norms and practices such as FGM, child marriage, girls’ education etc. These have led to my work around women’s rights.

“When I was 8 years old. I underwent female genital mutilation. In The Gambia, like many other countries where FGM is performed, the cutting is done on minors by an elderly woman with no medical background and under no medication.

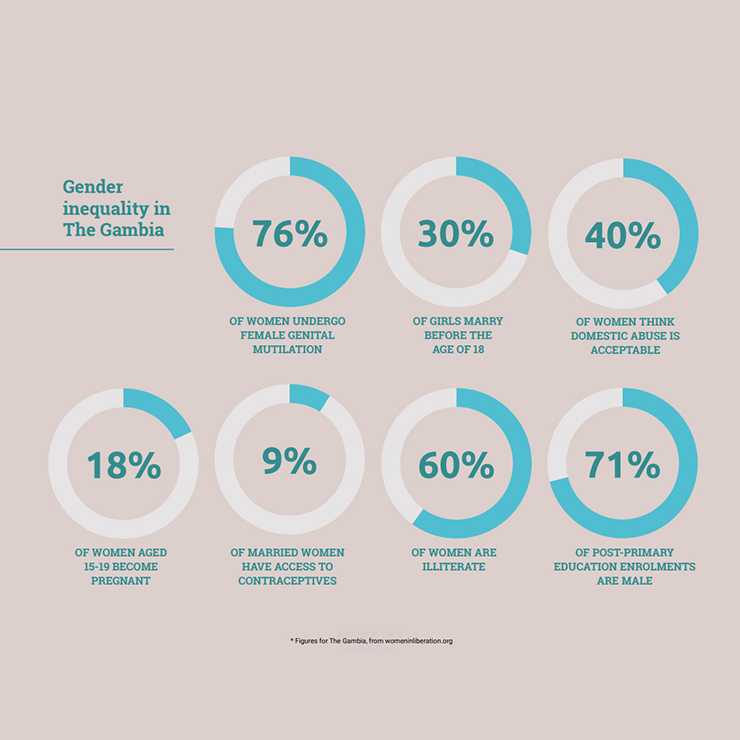

“One reason is that it is believed that when girls are not cut, they are not marriageable, they are unclean, and they will be promiscuous. In the Gambia, many people also believe that FGM is also a religious requirement, despite FGM predating Islam. These misconceptions and beliefs are deeply rooted and have been a major driving factor of the practice. Due to globalisation, women living with FGM are found across the world including developed countries such as the UK – as my work in Edinburgh proves.

“FGM has both short-term and long-term complications for women survivors. Families may face pressure by extended family members to practise FGM on their children born outside of their country of origin. This is what makes FGM an issue not just for practising countries, but for countries like the UK.

“Long-term complications include pain and blockages/scarring to the urinary tract and/or vagina, as well as infertility, painful sexual intercourse (for both men and women), and increased risk in childbirth. Many women also report that they are at increased risk of domestic violence – not because they don’t wish to be intimate with their partner, but due to the misunderstandings that occur surrounding their lack of enjoyment, and pain experienced during sex.

“The psychological complications are even broader, and many women, as well as feeling depressed, anxious, or afraid, experience phobias and panic attacks: further limiting their ability to flourish as they deserve.

“Furthermore, the main reason FGM is done is to deny us pleasure, which is my human right as a woman. That is something that continues to affect women throughout their adult life.

“FGM is internationally recognised as a violation of the human rights of girls and women. It reflects deeprooted inequality between the sexes and constitutes an extreme form of discrimination against girls and women.

As a young woman growing up, FGM was

very much part of my identity: everyone I knew round me had had FGM.

“I founded Women in Liberation and Leadership (WILL) in 2018 in The Gambia. WILL is a women-led organisation that focuses on empowering women and girls with knowledge around their sexual and reproductive health and rights. We create safe spaces to support young women to learn about their rights especially when it comes to relationships, their bodies and their role and responsibilities in society. We mentor young women on leadership roles and promote their access to higher education including STEM subjects.

“WILL also targets communities and works with them to change socio-cultural norms and practices that affect women and girls such as FGM and child marriage. Through this work, we work with community and religious leaders as agents of change and use the voices of young men as community ambassadors that support the eradication of FGM.

“Our community outreach activities include educating women about their rights and sharing information on different laws and legislation. WILL also provides psycho-social support to victims of sexual and gender-based violence to support women and girls, including those affected by FGM.

“Whilst FMG is illegal in The Gambia, the practice continues widely. There’s still big resistance to its abandonment and people advocating for the practice can receive backlash at the community level as well as on online platforms. Despite these challenges, the culture of silence around the practice has been broken. People now talk about FGM and many young people are being engaged in the advocacy.

“I am interested in women in leadership. It is important that we create role models for girls. By having more women in decision-making positions, we can also challenge the status quo. I will continue to use my voice and platforms to advocate for the rights and protection of women and girls. I am a big promoter of girls’ education, particularly access to higher education.

“Education has been the tool that has changed my mind and empowered me to use my voice to support the advancement of women and challenge socio-cultural norms and values that continue to hinder the progress of girls, stopping them from reaching their full potential.

“Fatou’s work may focus on FGM, but it’s clear that although FGM was done to her, it doesn’t define her."

And it is heartening to hear about how her personal life has resulted in happiness, filled with much hope and optimism for the future.

“Aside from my work, I love spending time with my family. I have four little boys and I love this because it means I will raise four boys who will one day grow up to be men who respect and value women and treat them as equal partners in society. From a very early age I am training my boys to respect and appreciate diversity and to treat everyone equally regardless of their background, gender identity and status.”

Read more about Fatou’s inspiring work, as well as her personal experience at: womeninliberation.org/blog.